Howard W. Campbell Jr. (Nick Nolte) says that one should beware who we pretend to be. We will become what we pretend.

Mother Night (1996), Keith Gordon’s adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s 1961 novel, doesn’t definitively clarify Campbell’s existential crisis. His fatalism at the end of the film, when he gets the reprieve he always thought he wanted, has less to do with his guilt over his actions for Germany during World War II and more about the sum total of loss and betrayal.

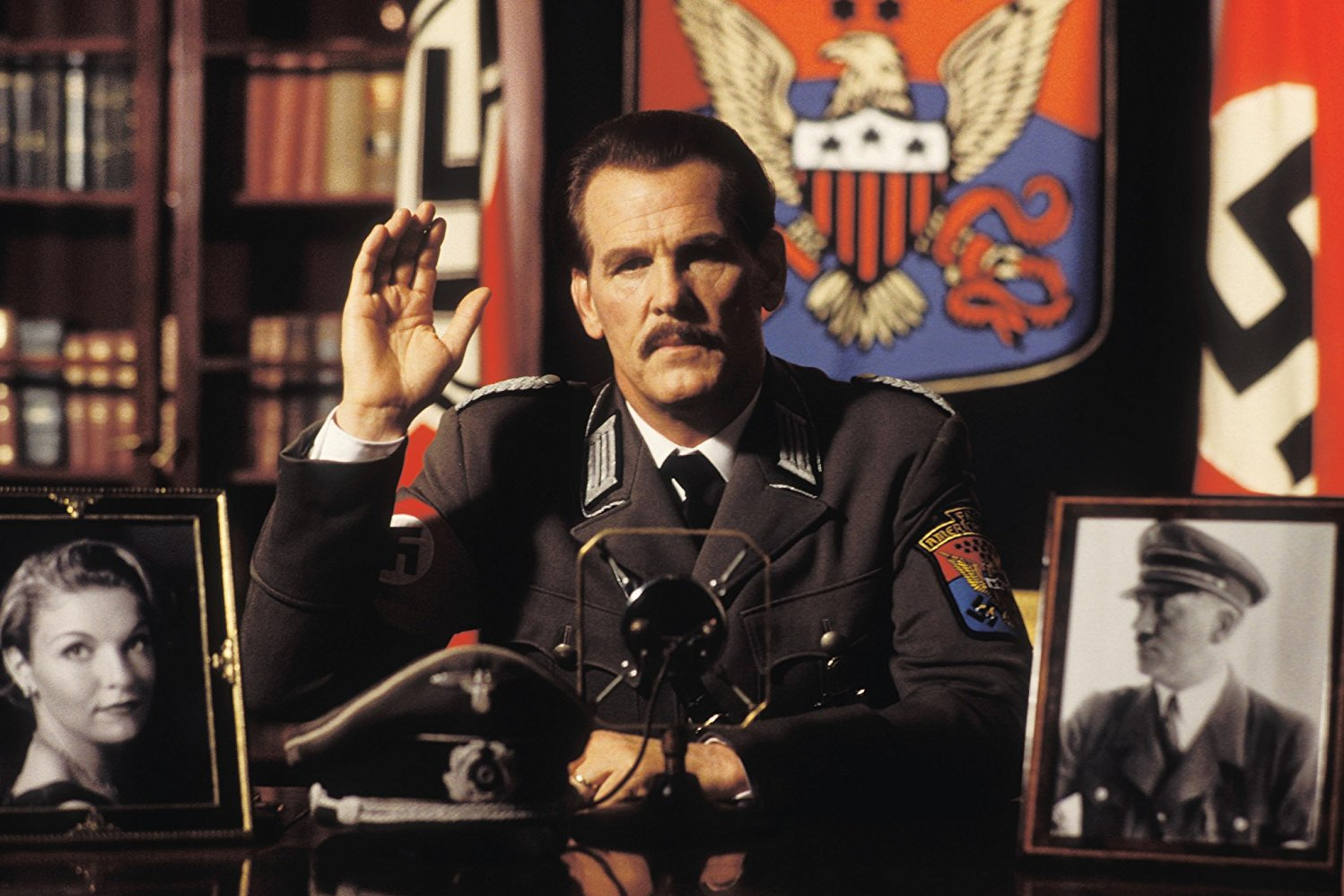

As an American agent, Campbell broadcast Nazi propaganda for four years. Much of the emphasis of his speeches blamed the Jews for getting the United States into World War II. He also systematically denigrates Jewish humanity, which results in their virtual annihilation. Campbell doesn’t see that particular result of his broadcasts. He was merely following orders from an American Agent, Frank Wirtanen (John Goodman): “Your role will remain classified, and Uncle Sam’s official position is that you are the scum of the earth.” Campbell calls Frank his “Blue Fairy Godmother”. Frank appears four times in the film, the last in the form of a letter.

Can the viewer, like the Israelis who have imprisoned Campbell, judge him guilty of war crimes? Does Campbell really believe he is responsible for accelerating the Holocaust? Can he be viewed as a tragic figure? On the one hand, he has created justifications for the Nazi policy to exterminate the Jews. But he has not intentionally done so.

Or was he pretending too hard? He may not have believed what he was saying but certainly embraced the idea of performing the “role” as a propagandist. This energy came from his vocation as a playwright before becoming an American agent. He had secured the role of a lifetime. At some level, he increasingly understands that this was his real problem or flaw.

But does Campbell kill himself, just as he is being vindicated (indeed, he might even become a hero, since he was the man who relayed secret information in his broadcasts which helped the Allies defeat Germany). I’ve wondered for years what his real reason was.

The film shows him confronting his past, his losses and many betrayals. He admits to having nothing to live for after his wife, Helga (Sheryl Lee), dies during the war in 1944. However, he pushes on living in what he describes as purgatory. He waits for redemption and appears to have attained it.

Campbell thinks his wife has returned to him. She didn’t die but looks the same after twenty years. Too good to be true. Not Helga, he finally learns, but her younger sister, Resi (also played by Sheryl Lee). Campbell believes he can maintain the illusion. Resi/Helga represents to the reappearance of his pet idea: the nation of two. While living in Nazi Germany as a successful playwright, he created a romantic cocoon described in one of his plays:

My dear sweet Eva, this is the only way I know how to make good the frightful wrong which has befallen us. It does not matter what lies ahead, for I have a full life behind me, all in those few sweet hours with you. I once told you that I would pledge my life for our nation of two, and reside there even in death, as surely as I reside in heaven when your arms are around me. Soon it will be time to keep that pledge, and I rejoice to think that earthly distractions will no longer intrude on my eternal devotion to you. From this moment forward our nation of two is the only country I will know.

When his conscious illusion of living with Resi is undermined (she’s working for the Soviet Union), Campbell finally cannot go on. In one of the film’s most compelling scenes, he stops on the sidewalk unable to move. There’s no where to go.

I was deposited on to the streets of New York, restored to the mainstream of life. I took several steps down the sidewalk when something happened. It was not guilt that froze me; I had taught myself never to feel guilt. It wasn’t the fear of death; I had taught myself to think of death as a friend. It was not the thought of being unloved that froze me; I had taught myself to do without love. What froze me was the fact that I had absolutely no reason to move in any direction.

The only thing he can do is turn himself over to Israeli agents and be tried for war crimes.

Perhaps Campbell’s real crime – his tragic flaw – is believing he could remain aloof from the gross realities of life. His performance as a propagandist reinforces his social and political detachment. He feels responsibility for the broadcasts and their consequences. But then he loses Helga and, later, Reni. He tries to evade the world in general, hiding out in New York City. This isn’t enough, finally.

He couldn’t believe in his innocence. Neither could he live (literally) with the reprieve offered by Wirtanen. His nation of two became a nation of none when he hangs himself in the cell with typewriter ribbon.